Author of the elaboration: prof. dr hab. Stanisław Skompski

A significant feature of the Palaeozoic inlier, which can be spotted already when analysing the Cambrian history of the area, is its differentiation into two parts: the southern Kielce Region and the northern Łysogóry Region. This differentiation occurs at several levels; it refers to differences in lithologies and tectonic history (e.g. Czarnocki 1919, 1957; Samsonowicz 1926; Szulczewski 1977). Tectonically, the boundary between the regions is the Holy Cross Fault (Fig. 2). In terms of facies, the boundary separating areas of different sedimentation and distinct diastrophic rhythms (presence of unconformities and stratigraphic gaps) is much more difficult to determine, particularly due to the fact that its position varied in time and usually overstepped the tectonic boundary. In order to eradicate these terminological discrepancies, in this book the term Łysogóry (or Kielce) Fold Belt will be used for tectonic units and the term Łysogóry (or Kielce) Region will refer to facies areas. The sub-division into lower rank units is presented in the chapter devoted to the tectonic history of the Holy Cross Mountains (Fig. 2).

A basic problem that significantly influences the interpretation of the geological history of the Holy Cross Mountains is the choice of an hypothesis regarding the palaeogeographic relationships of the two regions. An extreme older hypothesis suggested that both regions were located in close vicinity to one another throughout the Palaeozoic, and that the development of different facies was influenced by the rate and course of subsidence and by different source areas of the clastic material (Dadlez et al. 1994; Żelaźniewicz 1998; Kowalczewski 2000; Jaworowski and Sikorska 2006). This theory has been confirmed by deep seismic soundings, which have shown that in both the Łysogóry and Kielce regions (the latter lies in the northern part of the Małopolska Block), the structure of the deep basement is very similar to the crustal structure known from the East-European Craton (Malinowski et al. 2005). A much more recent hypothesis assumes that the regions developed independently of one another and merged during the Variscan Epoch (Lewandowski 1993). There are a number of intermediate hypotheses, presuming, for instance, earlier collision times (see Pożaryski 1991; Belka et al. 2002; Nawrocki et al. 2007). The arguments for each of these hypotheses will be presented in the final part of this chapter, after presenting the facies development of the Cambrian to Silurian succession.

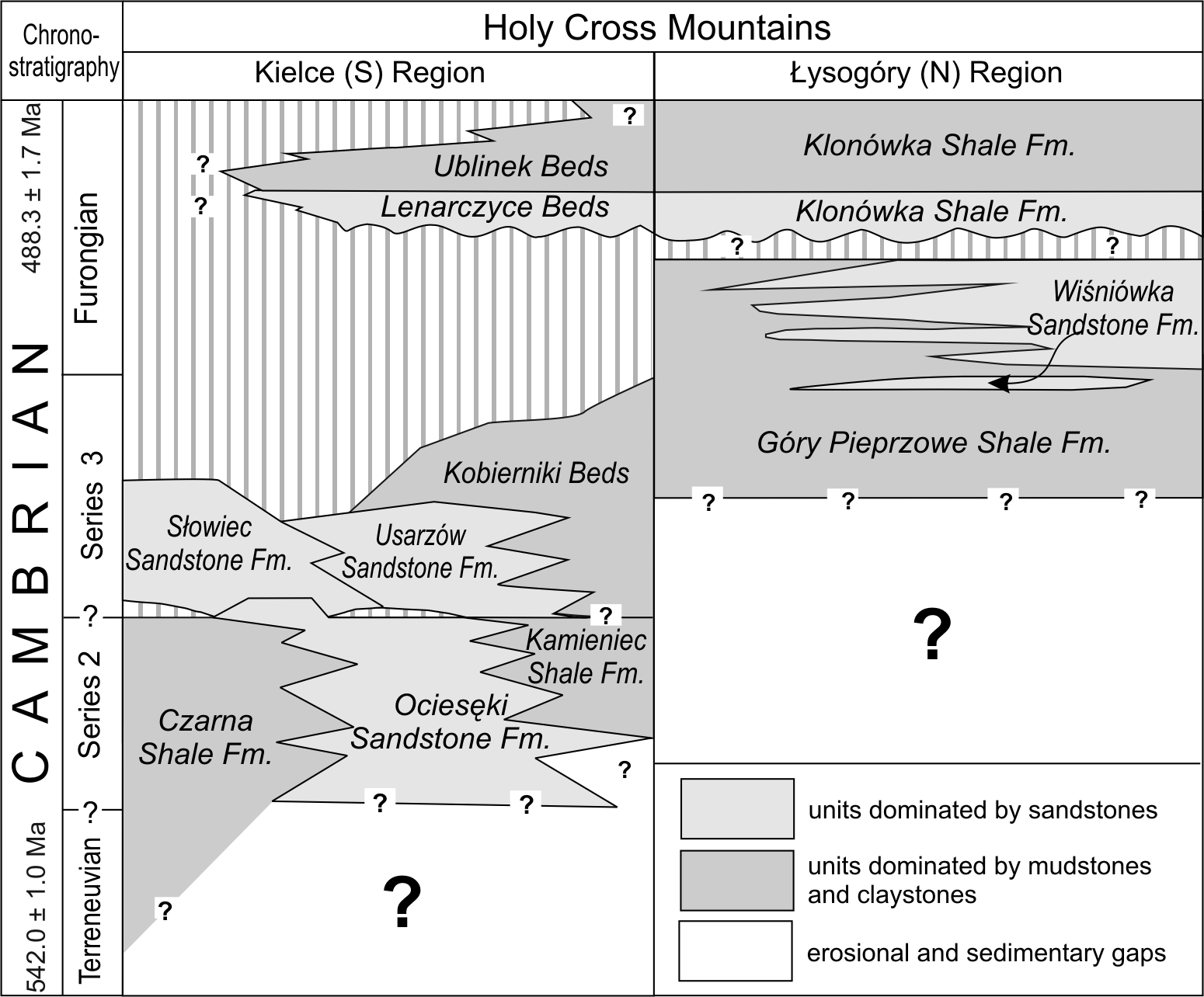

The oldest rocks of the Holy Cross Mountains, exposed in the village of Kotuszów close to the town of Staszów, are Cambrian clay and mud shales with very rare fossils (Fig. 2). Although their occurrence is slightly to the south of the Palaeozoic inlier exposures, within the Carpathian Foredeep, they represent the lowermost Cambrian Czarna Shale Formation which has been recognised in many localities in the southern part of the inlier (Orłowski 1975b; Kowalczewski et al. 2006). The higher part of the Cambrian succession includes clastic rocks of different grain sizes; therefore the lithostratigraphic scheme contains numerous sandstone and clay-mudstone formations. The clay-mudstone formations are rather monotonous and have few specific features, whereas the formations dominated by sandstones differ from each other in lithological composition, sorting, matrix type, and degree of bioturbation, that is the effects of life activities of various skeletal and non-skeletal invertebrate organisms. Particular examples include two formations, Ociesęki and Wiśniówka. In the first unit, bioturbation is very common but rather poorly preserved. The bioturbated strata, interbedded with shales, were formed during anoxic events (Stachacz 2012). In the second formation, less frequent but perfectly preserved traces of resting, moving and feeding trilobites (Radwański and Roniewicz 1963; Orłowski et al. 1970) compose the Wiśniówka ichnocoenosis which is a geological site of worldwide significance.

The Wiśniówka Formation differs from other Cambrian units in yet another feature. It is composed of extremely hard and resistant quartzites that build the main ranges of the Holy Cross Mountains: the Masłowskie, Łysogórskie and Jeleniowskie ranges, which are sometimes informally referred to the Main Range. The Orłowińskie and Cisowskie ranges, located to the south and composed of older Cambrian rocks, are much lower; nevertheless, being the basic elements of the Klimontów Anticlinorium, they rise above the rocks of the Kielce-Łagów Synclinorium, the northern part of the Kielce Region.

Cambrian rocks with a total thickness estimated at 2.5–3.5 km dominate the area of the Palaeozoic inlier (c. 40%) but are not evenly distributed between the two regions. Until recently it was assumed that strata recording the first three Cambrian series occur in the southern region (Fig. 2), whereas the northern region contains Cambrian Series 3 and Furongian rocks. New discoveries indicate that Furongian rocks are also present in the Kielce Region (Szczepanik et al. 2004) and are similar to contemporaneous strata from the Łysogóry Region. Nevertheless, the general discrepancy in the distribution of contemporary Cambrian rocks among the northern and southern regions of the Holy Cross Mountains hampers comparison of the sedimentary conditions in both areas. Usually, these settings are interpreted to generally represent a siliciclastic shelf, present at greater depths when the clay-mudstone formations were deposited and shallower during sandstone sedimentation. The relative abundance of sedimentary structures permits a more detailed interpretation of selected sandstone formations, of which some, such as the Wiśniówka Formation, contain features of relatively shallow deposits recording storm-related deformations (Studencki 1994; Jaworowski and Sikorska 2006). On the other hand, a high degree of recrystallization of the sandstone matrix has obliterated their primary sedimentary structures, meaning that sedimentological interpretations are highly hypothetical, even inducing extreme opinions on the deep-marine nature of the entire Cambrian succession in the Holy Cross Mountains area (Malec 2004). Variable interpretations of the Cambrian sedimentary settings were also linked with the progressive detailed recognition of the spatial relationships between the lithostratigraphic units. Initially, temporal interfingering of the clay-mudstone and sandstone units was assumed and, accordingly, changes of the depths of the sedimentary environment were invoked. A more detailed understanding of the geographic distribution of particular units and their age has demonstrated lateral intergradations between the fine- and coarse-grained formations, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Lithostratigraphic scheme of the Cambrian in the Holy Cross Mountains (modified after Orłowski 1975b and Kowalczewski et al. 2006)

In this context, highly probable is the interpretation of Jaworowski and Sikorska (2006), in which the sandstone units are related to the crests of tilted basement blocks, located on the margin of the East European Craton. The clay and mudstones facies would in this case develop in the subsided parts of the blocks.

Progressive identification of Cambrian strata would not be possible without an improved biostratigraphy of the Cambrian System. It is based on trilobites and recently also on a group of enigmatic microfossils of plant origin, the Acritarcha (Orłowski 1968, 1985a, 1985b, 1988; Szczepanik 2001; Żylińska 2001; Żylińska and Szczepanik 2009; Żylińska 2013). The trilobites allow us not only to determine the detailed age of the beds in which they occur, but also record the complex and variable palaeogeographic relationships of the Holy Cross Mountains basin with nearby palaeocontinents and terranes: Gondwana, Avalonia and Baltica (Żylińska 2001, 2013; Alvaro et al. 2013). Analysis of acritarch assemblages requires specialist laboratories; in turn, trilobite fossils can be found by persistent and observant collectors. Trilobite fossils are rather common in the exposures within the Klimontów Anticlinorium. Each find may be of scientific value, and we would kindly appreciate it if information about new finds would be sent to scientists that conduct systematic and specialist studies of Cambrian trilobites.