Author of the elaboration: prof. dr hab. Stanisław Skompski

Rocks of the new sedimentary cycle in the Holy Cross Mountains, which begin the Permian-Mesozoic succession that was folded by the end of the Cretaceous in one of the phases of the Alpine Orogeny, lie with distinct angular unconformity on the older eroded basement. In its most informative exposure, this unconformity is known from Zachełmie Quarry and it is slightly less clearly visible in Jaworznia Quarry near the village of Piekoszów, Doły Opacie Quarry near the town of Kunów, and at present is progressively being exposed in Wola Quarry near the village of Kowala. In other locations its presence can only be interpreted by comparing the bedding orientation of strata in neighbouring exposures.

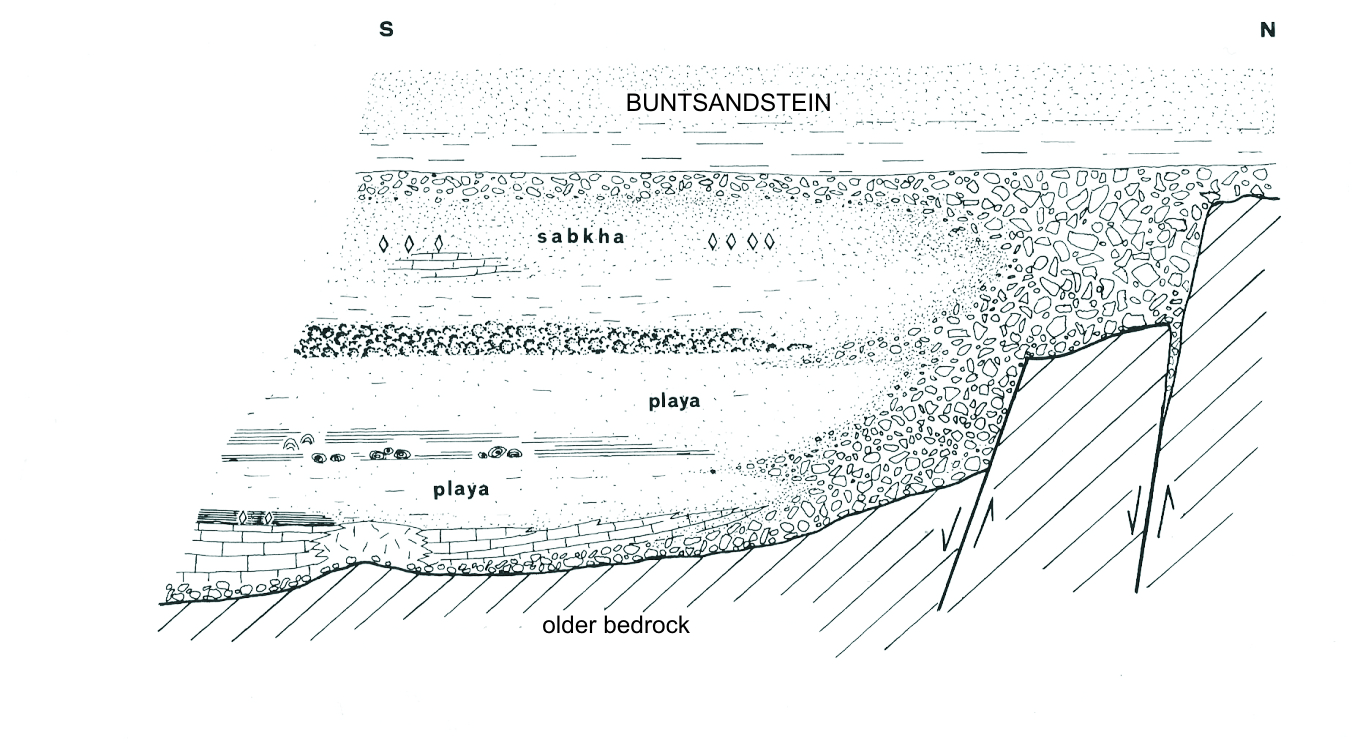

Strata that overlie the Variscan erosion surface were deposited in a continental setting, and a lack of fossils hampers a correct determination of their stratigraphic position. According to traditional criteria, sediments containing only local material from the eroded basement were treated as Permian in age, whereas those with material from distant sources (quartz, mica) were classified as Triassic. It is clear now that this criterion does not reflect the real stratigraphic assignment of the deposits; however, so far there are no explicit and definitive solutions to this problem. Certainly, a Permian age can be attributed to the coarse-grained units of conglomerate localized at the foots of the Variscan mountain ranges. The best examples include the Zygmuntówka Conglomerates, exploited for several hundreds of years in Zygmuntówka Quarry near the town of Chęciny. Such deposits gradually filled mountain valleys and levelled height differences (Fig. 7). The progressing process of peneplanization did not yet reach its final stage, that is a flat morphological surface, when a sea appeared in the western margin of the “Holy Cross uplands”. Through narrow bays it intruded onto a land which gradually became a peninsula. Continental coarse-grained deposits lying on the bay margins were partly transformed by the sea approaching from the north-west, in which shallow-marine sediments were formed (Zechstein facies), either covering the conglomerates or interfingering with them (Fig. 7)

Fig. 7. Scheme of facies diversity in the Permian of the Holy Cross Mountains, based on the successions exposed in the Gałęzice-Bolechowice Syncline. An exclusively conglomerate succession is typical of Zygmuntówka Quarry, whereas a succession with the prevalence of marine facies with bryozoan, algal, laminated limestones, playa and sebkha facies is typical of the western part of the syncline near Gałęzice (after Bełka 1991)

The presence of fossils in the marls and limestones deposited in the axial parts of the bays indicates a late Permian age (Kowalczewski 1978, Rubinowski 1978). Correlation with logs from Central Poland has revealed that they correspond to evaporitic cyclothem PZ1 (Werra), reflecting a vast marine transgression. The subsequent three transgressions had a much narrower lateral range, therefore the younger cyclothems PZ2, PZ3 and PZ4 have been recognised only in logs of boreholes drilled at a distance of over ten kilometres to the south-west in relation to the Palaeozoic inlier of the Holy Cross Mountains (Kuleta and Zbroja 2006).

The best locality in which to become acquainted with Permian rocks of the Holy Cross Mountains is the vicinity of the village of Gałęzice, where an almost complete succession of strata can be recognised, formed in settings varying from continental towards a deep, narrow marine bay (Gałęzice Bay). Slightly different aspects of sedimentation can be observed in Kajetanów Bay, located north of the city of Kielce near the village of Kajetanów, where the succession exposed in an abandoned quarry characterizes a poorly oxygenated, deeper sedimentary environment, unknown from the Gałęzice area.

A short-term episode of marine sedimentation (several million years in the latest Permian) terminated the exciting Palaeozoic history of the Holy Cross Mountains. The retreating (drying-up) Permian sea left a flatland with intermittent inliers, windswept and burnt under the tropical sun. Another 180 million year had to pass until the area again became mountainous.